Taking Shape

Activities to Develop Geometric and Spatial Thinking

Enrich Your Geometry Curriculum and Extend Your Students’ Spatial Reasoning

Copyright

2016

Grade(s)

K - 12

Delivery Method

Blended (Print & Digital)

Research shows that children with good spatial skills perform better in mathematics overall. This research-based resource is a unique blend of professional learning and classroom activities. It includes:

- 32 field-tested and research-based activities designed to appeal to young children

- Guided lesson plans, including 15 videos, that serve as models for best practice in instruction

- Tips on observing, questioning, and assessing young children’s geometric and spatial thinking

- Free access to website with videos, curriculum correlations, line masters, and observation guides

Authors

Joan Moss

Joan Moss is an Associate Professor in the Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development at the Institute of Child Study at OISE/UT. A former elementary school teacher, her research has focused on the design of developmentally based curricula highlighting areas of mathematics that are traditionally challenging for students. Her research on early algebra has appeared in numerous international publications. Since 2011, Joan has been a co-Principal Investigator of the Math for Young Children (M4YC) project, which supports the teaching and learning of spatial reasoning in Early Years classrooms. Most recently, she collaborated with the Robertson Program for Inquiry-Based Teaching in Math and Science to expand the M4YC initiative to include collaborations in four First Nations communities and with the Rainy River District School Board. Joan has won many honours and awards, including the award for Distinguished Contributions to Teaching.

Catherine D. Bruce

Catherine D. Bruce is an Associate Professor at the Trent University School of Education and Professional Learning. Catherine is a co-Principal Investigator of the Math for Young Children (M4YC) project. She won a SSHRC Award in 2013 to continue this research into early mathematics and young children’s spatial reasoning. A former teacher, Catherine has been studying teaching and learning for 25 years. She teaches mathematics methods courses at Trent where she brings her passion for mathematics teaching and learning to teacher candidates. In 2012–2013, Catherine was honoured to receive the prestigious Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA) teaching award. Additionally, she received the 2015 International Eduardo Flores Leadership Award for her contributions to action research locally, nationally, and internationally. Key areas of research include teacher and student efficacy, the effectiveness of alternative models of professional learning for teachers, the use of technology in the mathematics classroom, as well as teaching and learning in the difficult-to-learn areas of fractions and algebra. Her awesome family of boys keeps her on her toes.

Bev Caswell

Bev Caswell is the Director of the Robertson Program for Inquiry-Based Teaching in Mathematics and Science at the Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto). She works collaboratively with educators to design participatory learning environments that invite students to engage with ideas and develop a deeper understanding of mathematics concepts. Bev completed her doctoral research focusing on equity in mathematics. She is dedicated to working with students typically underserved by the educational system. Bev has ten years’ experience as an elementary school classroom teacher and fifteen years’ experience in pre-service and in-service teacher education. She is married and is the mother of four dynamic individuals.

Tara Flynn

Tara Flynn is an educator, author, and editor who has worked with Dr. Cathy Bruce in the fascinating world of mathematics education research since 2007. As Project Manager and Research Officer, Tara has worked with countless dedicated and innovative educators, and has been an integral member of the Math for Young Children (M4YC) team since the project’s inception. She has co-authored several publications on young children’s spatial reasoning and has presented widely on this topic. As an editor, Tara cut her teeth at Alternatives Journal, and more recently has edited numerous teacher resources in mathematics education. She is the awestruck mother of a 20-year-old son. Tara has spent the past nine years trying to explain to her family what she does for a living, and is really hoping that this book will help to answer that question.

Zachary Hawes

Zachary Hawes is a Ph.D. candidate in the Numerical Cognition Laboratory at the University of Western Ontario. Prior to this, he completed his M.A. and teacher training at the University of Toronto’s Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study. Not wanting to leave the Institute, and having developed a keen interest in how children learn mathematics, Zack stayed on to work as a research officer for four years. His past and current research is broadly focused on understanding the development of mathematical thinking and ways in which to improve such learning. More recently, he is interested in studying the relationship between spatial and numerical cognition, with the ultimate goal of using this information to leverage classroom instruction. Other interests include painting, traveling, and playing basketball.

Testimonials

Taking Shape authors are recognized leaders in spatial reasoning research who work directly with children and teachers. This text is simultaneously a research report and a resource package. Readers are provided with a focused introduction to key research findings and generous descriptions of classroom activities. They are invited into rich discussions of how emergent insights into spatial reasoning might contribute to task designs, how designs might be enacted and adapted, how teachers might watch and listen, and how student actions might be interpreted. In brief, the text manages to go far beyond the “how to,” involving practitioners in serious considerations of what spatial reasoning is all about and why that matters.

Brent Davis, Professor, Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary

This is an indispensable resource for any K–2 teacher. The authors offer creative lessons aimed at developing children’s spatial reasoning, which will help them learn and love mathematics. These lessons are based on solid research fi ndings as well as sound pedagogical principles. Indeed, the research is absolutely clear: using these lessons will help bring curiosity and confidence into your mathematics classroom and prepare your children for success in a broad range of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics) careers.

Nathalie Sinclair, Professor, Simon Fraser University, Canada Research Chair in Tangible Mathematics Learning

Foreword

Numeracy. For many people, that’s another name for “mathematics.” Many people commonly assume that mathematics, especially early mathematics, is about counting and arithmetic. From this perspective, measurement, geometry, and graphing are minor parts of the curriculum, often left to the end of the year when little time is available to spend on them. Does that lack of exposure really hurt children? Are those topics truly important?

In a word, yes. In this well-written book, Joan Moss, Cathy Bruce, Bev Caswell, Tara Flynn, and Zack Hawes show clearly that spatial reasoning is critically important, that geometry is more than naming shapes, and that learning number and arithmetic by way of shape and space has substantial advantages.

To their credit, in Part I of Taking Shape, the authors take readers inside the processes of spatial reasoning. They give clear explanations and include just enough research to support why and how the processes are important to mathematics and subjects beyond mathematics. Perhaps most important, they provide concrete examples that illustrate the spatial reasoning processes and how children might learn pertinent skills.

The authors show that spatial reasoning contributes to math- ematical ability. This observation is significant: spatial reasoning is a process that is distinct from other types of thinking, such as verbal reasoning (Shepard & Cooper, 1982); it also functions in distinct areas of the brain (Newcombe & Huttenlocher, 2000; O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978). And, as the authors point out, mathematics achievement is related to spatial abilities (Ansari et al., 2003; Fennema& Sherman, 1978; Guay & McDaniel, 1977; Lean & Clements, 1981; Stewart, Leeson, & Wright, 1997; Wheatley, 1990). Further, important equity issues are at play here. We know, for example, that girls, certain other groups that are under-represented in mathematics, and some individuals are harmed in their progression in mathematics due to lack of attention to spatial skills; they would benefit from more geometry and spatial skills education (see, for example, Casey & Erkut, 2005)

However, the relationship between spatial thinking and mathematics is not straightforward, and this book makes it clear which types of spatial thinking the authors want children to develop. For example, some research indicates that students who process mathematical information by verbal-logical means outperform students who process information visually (Clements & Battista, 1992; Sarama & Clements, 2009a). Clearly, the types of spatial competencies matter. Students in those studies “who process information visually” are relying on primitive processes, such as “seeing” surface features of problems (which, in the book, are called “pictorial representations”). Instead, the authors help students develop spatial reasoning in order to develop “visual-schematic representations” in two major types: spatial orientation and spatial visualization (Bishop, 1980; Harris, 1981; McGee, 1979). This kind of high-quality education helps children move beyond simple surface-level visual thinking as they learn to manipulate dynamic images, as they enrich their store of images for shapes, and as they connect their spatial knowledge to verbal, analytic knowledge.

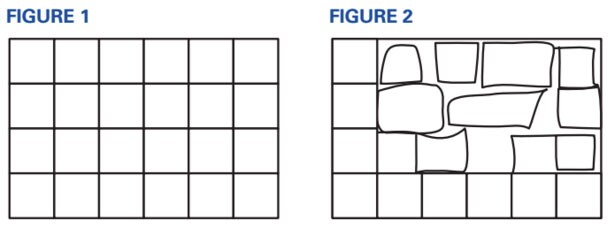

Skeptics might think: “Really? You need spatial knowledge beyond what all children know to solve problems in arithmetic and algebra?” The answer is yes. Consider the research that Julie Sarama and I have done on elementary students’ knowledge of area (Clements & Sarama, 2014; Sarama & Clements, 2009a). Students are often asked to count the number of squares to figure out the area of a region, as shown in Figure 1, below. They learn to use a formula, A = L × W. Later, however, many students forget which formula is for area and which is for perimeter. Or, when asked to explain why 4 × 6 “works” to find the area, they do not know. Why? Although adults may understand the rows and columns in Figure 1, many students do not. Asked to simply copy Figure 1, many students, even intermediate students, draw images such as that in Figure 2. Some learners do not understand the spatial structure of even simple arrays.

How then should we help children develop such spatial reasoning? Part II of Taking Shapeshows how. It provides well-organized, developmentally appropriate, and engaging sets of activities that address the five particular aspects of geometry that the authors identified in Part I.

Number and operations may be the most important focus of early mathematics (National Research Council, 2009), but we ignore ngeometry and spatial reasoning at our peril. These subjects are critical in and of themselves. Just as important, however, is this finding: children will not learn number and operations, which includes solving problemsn involving these topics, well unless they also learn spatial reasoning.

Douglas H. Clements

Professional Service

Did you know that spatial reasoning is an important predictor of achievement in many STEM careers?

While we talk about spatial reasoning what does the term really mean? In this one-day session, you not only learn what it means but also how to develop it in your young students. This highly interactive session focuses on five key strands related to geometry and spatial reasoning:

- Symmetry

- Composing, Decomposing, and Transforming Two-Dimensional Figures

- Composing, Decomposing, and Transforming Three-Dimensional Objects

- Locating, Orienting, Mapping, and Coding

- Perspective Taking

Preview Print Products

Sample Pages

Table of Contents

Part 1: Background and Research

Chapter 1: Shaping Young Minds: Why We Care About Spatial Reasoning in the Early Years

- What Is Spatial Reasoning?

- Why Math in the Early Years Is So Important

- Why Teach Spatial Reasoning?

Chapter 2: What Makes This Book Different From Other Geometry resources?

- 1. An Expanded Vision of Geometry

- 2. A Deep Focus on Five Particular Aspects of Geometry

- 3. An Emphasis on Playful Pedagogy

- 4. A Research Focus: Tested Educational Benefits

Chapter 3: A Review of Spatial Reasoning Concepts and Processes

- 1. Visualization

- 2. Mental Rotation

- 3. Visual-Spatial Working Memory

- 4. Information Processing

- 5. Spatial Language

- 6. Gestures

Chapter 4: How to Use This Book

- Implementation Suggestions

- How Is the Book Organized?

- Where to Begin?

- What Next?

- Classroom Organization

- Observing Student Thinking: Junior Kindergarten to Grade 2

- Assessment Suggestions

Part 2: Activities

Section A: Symmetry

- Lesson 1: Let’s Learn About Symmetry

- Lesson 2: Pattern Block Symmetry Puzzles

- Lesson 3: Pentomino Symmetry Games

- Lesson 4: Symmetry on Grids—Integrating Location and Number

- Lesson 5: Grid Symmetry Game

- Lesson 6: Hole-Punch Symmetry Challenge

- Lesson 7: Symmetry Card Games

Section B: Composing, Decomposing, and Transforming Two-Dimensional Shapes

- Lesson 1: Find the Magic (Pentomino) Keys

- Lesson 2: See It, Build It, Check It—Pattern Blocks

- Lesson 3: The Hexagon Card Game

- Lesson 4: Can You Draw This?

- Lesson 5: Can You Cover It?

- Lesson 6: The Square Mover

- Lesson 7: The Shape Transformer

Section C: Composing, Decomposing, and Transforming Three-Dimensional Objects

- Lesson 1: The Cube Challenge—Discovering Three-Dimensional Congruence

- Lesson 2: Build It in Your Mind

- Lesson 3: Box or Not?

- Lesson 4: See It, Build It, Check It—Interlocking Cubes

- Lesson 5: Building Rules!

Section D: Locating, Orienting, Mapping, and Coding

- A Focus on Coding

- Lesson 1: Introductory Barrier Game

- Lesson 2: Secret Shape Code

- Lesson 3: What Did You Make?

- Lesson 4: Pathway Moves

- Lesson 5: Paper Pathways

- Lesson 6: Secret Code Game

- Lesson 7: Pathway Coding Game

Section E: Perspective Taking

- Lesson 1: Mother Bird Finds a Sculpture

- Lesson 2: Shoebox Goggles

- Lesson 3: Build It, Photograph It, Make It

- Lesson 4: Crazy Creatures

- Lesson 5: What Do You See?

- Lesson 6: Secret LEGO® Buildings

Appendices

- One-to-One Interview Tasks and Observation Guides

- Index of Lessons by Grade Level

- Index of Lessons by Math and Spatial Reasoning Focus

- References

- Authors

- Credits

How can I buy?

Purchase by Phone

Contact customer service at

1 (800) 361-6128