Well Aware - Developing Resilient, Active, and Flourishing Students

Device

Pearson Canada

Author(s)

Patrick Carney

Mental health concerns, particularly those relating to children and youth, are increasing in number and complexity. In the face of this serious issue, how can we as educators help our students to be well—mentally, physically, and emotionally?

Beyond the media’s focus on symptoms and disorders, we are seeing a shift toward understanding that developing positive mental health is foundational to academic achievement, effective life skills, and overall well-being for all students. This book provides you with the research-based evidence, practical tools, and ready-to-use strategies to help create a culture of positive mental health in your classroom. It reveals how, by working together, teachers and the larger educational community can make a difference to a student’s mental health.

Features & Benefits

Educators have always been concerned with students’ well-being and healthy development. What is new is a recognition that we need to be

- more informed about mental health promotion

- more tactical about promoting healthy habits and addressing problems early

- more focused when using evidence-based strategies at the classroom, school, and community levels

How can this resource help you? The goal is to provide you with the research-based evidence, tools, and strategies to help support students’ healthy development in practical and effective ways. It is difficult to overstate the difference a teacher, or a school, can make in a child’s or youth’s mental health — not through expensive or sophisticated interventions — but through compassion, inclusion, encouragement, and effective instruction.

Authors

Patrick Carney, Ph.D.

Dr. Carney is a Fellow of the Canadian Psychological Association, an honour awarded to him in recognition of his outstanding service and contributions to the field of educational psychology. Dr. Carney is a passionate spokesperson and advocate for positive mental health for all students. His dedication and leadership in this field is reflected in his many roles, including President of the Association of Chief

Psychologists with Ontario School Boards and two terms as President of the Canadian Association of School Psychologists. In his role as Chief Psychologist, Simcoe County Roman Catholic District School Board, Dr. Carney works with students, teachers, and their parents to develop positive mental health using many of the evidence-based strategies outlined in this text.

Reviewers

Dr. Sue Ball

Chief Psychologist, York Region District School Board

Newmarket, ON

Dr. Jennifer Batycky

Principal, Rosscarrock School

Calgary Board of Education

Calgary, AB

Steve Charbonneau

Superintendent of Elementary Schools, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic District School Board

Barrie, ON

Dr. Bruce Ferguson

Senior Consultant, Community Health Systems Resource Group

The Hospital for Sick Children

Toronto, ON

Paula Jurzcak

Child and Family Therapist

Richmond, BC

Joyleen Podgursky

Learning Support Team Co-ordinator

Prairie South Schools

Moose Jaw, SK

Taunya Shaw

School Psychologist, School District #36

Surrey, BC

Dr. Suzanne L. Stewart

Associate Professor, OISE/University of Toronto

Toronto, ON

Testimonials

The book “Well Aware: Developing Resilient, Active, and Flourishing Students” lends itself perfectly to the philosophy behind the Trillium Lakelands District School Board approach to health and well-being, ‘Feed all Four’. This approach stresses the importance of connecting, relating, and teaching to the ‘whole child’ by using the curriculum as the vehicle. Its foundation is based on Maslow's hierarchy of needs and the First Nations medicine wheel, and emphasizes the importance of balance between body, mind, spirit, and emotion for students and also for our staff.

The Well Aware resource supports the foundation of Feed All Four which moves away from the idea of mental health as ‘illness,’ and moves toward the fundamental importance of prevention. The focus on balance and positive school culture “compassion, inclusion, encouragement, and effective instruction” for example, are all preventative strategies that can work to protect our youth from becoming the ‘one-in-five statistic’ impacted by mental health issues in Canada.

This book also emphasizes the importance of staff wellness which is an integral part of Feed All Four. Flourishing students are developed, in part, by flourishing teachers.

The TLDSB Feed All Four team has introduced the Well Aware resource during presentations, PLCs, and to help develop school improvement plans. This resource was also reviewed with the TLDSB Mental Health Steering Committee, some of whom chose to purchase the book immediately. We have recently purchased a copy for every principal in our board and these will be distributed at a principal’s meeting in April to support our Feed All Four approach to health and well-being.

Dave Lyons

Healthy Active Living Consultant

Cheryl Roffe

Manager of Mental Health and Student Well Being

Heather Truscott

Special Programmes Consultant

Resource Overview

“The role of the school has been regarded both nationally and internationally as an important environment for promoting the psychological wellness and resilience of children and youth.”

— Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health, 2013, p. 20

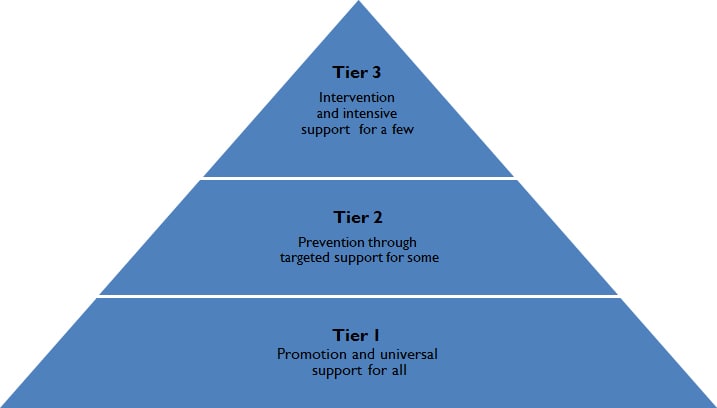

The focus in this resource is on what has been called Tier 1, in the three-tier model shown below. The emphasis is on mental health promotion and universal support for all students through teaching, modelling, and supporting the development of key skills and healthy behaviours. Targeted support and intervention for mental health problems fall into Tiers 2 and 3, largely beyond the scope of this resource.

Three Tiers of Help for Students

Tier 1

At this level, schools promote mental health for all students. Consider this example. We know that all students experience nervousness to some degree, and all students have anxiety-provoking experiences at some point in their lives. Schools can help students recognize anxiety and acquire the resiliency skills to navigate through these challenges. In the classroom, we can teach students a wide range of healthy behaviours and provide them with opportunities and encouragement for practising them.

Here is a second example. Social anxiety is a common disorder among youth. We know that experiences of situational anxiety are common to some degree in all of us, and most students will benefit from learning concepts of physiological arousal, relaxation skills, and even skills for public speaking. All of these can be considered Tier 1 mental health promotional activities.

Tier 2

At this level, school staff partner with professional staff at the school board to catch common behavioural, emotional, and social problems. Together, using a small-group format, they provide programs that teach specific social and emotional skills to those at risk before these students acquire more significant problems or diagnosable conditions. For example, school and mental health professionals commonly conduct small-group sessions that teach skills for self-regulation, such as simple breathing exercises, mental imagery, and positive self-talk.

Tier 3

At Tier 3, students experience difficulties to such a degree that their normal functioning is seriously hampered, and learning is compromised. These students require more intensive intervention involving mental health professionals. Teachers and other school staff work with mental health professionals to provide a system of wraparound support, accommodation, and welcome for students as they practise their self-regulation and other coping skills in the school environment. The term wraparound refers to the support that an interdisciplinary team of teachers, parents, and professionals provide to support a student with complex needs.

This is a framework for understanding and supporting the development of positive mental health for all students. It provides a brief overview of the essential elements that constitute positive mental health and introduces the foundations that we as educators can cultivate to help students achieve that goal.

What Is Positive Mental Health?

First, let’s look at what we mean by positive mental health. Positive mental health has been defined by the Public Health Agency of Canada as “the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections, and personal dignity” (Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], 2006, p. 2).

A key phrase in this definition is “a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being.” Positive mental health is well-being, and we will use the two terms interchangeably in this resource. The idea of well-being means that positive mental health goes beyond the more clinical definition of mental health as the absence of illness or disorder. A state of well-being encompasses a sense of enjoyment in life, of realizing our potential, meeting challenges, being productive, respecting ourselves and others, and making a positive contribution to our communities.

Respect for “culture, equity, social justice, interconnections, and personal dignity”—none of that is new to you as an educator. Many of the values and attitudes you are already fostering are directly linked to positive mental health. Helping students understand these links and take charge of them to foster their own well-being is the ultimate goal.

We can help students learn to recognize feelings and regulate their emotions so that they are less likely to get caught in emotional distress. We can help them develop social and emotional skills to build positive relationships and community connections to support wellbeing. When students come to understand that positive mental health is a goal for which to strive and that all of us will experience stress and challenge throughout our lives, they can become better able to manage their emotions and deal with issues. They can become more resilient and focused on achieving their potential.

Promoting Positive Mental Health

Effecting this change in understanding of mental health requires active promotion. Mental health promotion requires a different mindset from mental health intervention (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2009). Mental health intervention is important for students who have mental health disorders or who may be at high risk of developing mental health disorders. These students need specific support and referral to mental health professionals.

With mental health promotion, the focus is on opportunities for all students to celebrate and develop their gifts, be physically active, achieve a true sense of belonging, experience joy, and learn social and emotional resiliency skills for their lives ahead. A mental health promotion mindset helps to reduce the number of individuals who will develop mental health disorders and to provide optimal environments for all to flourish, including those with challenged mental health.

Mental health promotion requires work at all levels of education— national, regional, local, and classroom. The Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health, for example, has created an internationally recognized framework to support the promotion of comprehensive school health (Joint Consortium for School Health [ JCSH], 2009). The framework includes four integrated pillars that work to support positive mental health outcomes: social and physical environment, teaching and learning, partnerships and services, and healthy school policy.

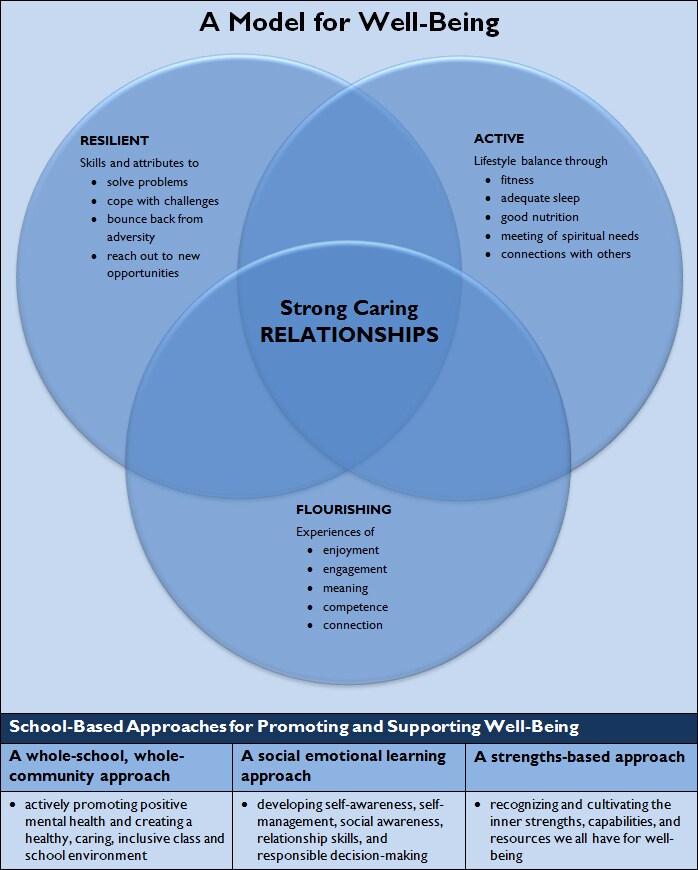

This book follows a model similar in its integration of factors that contribute to positive mental health. In our model, which is designed for school-based implementation, we outline three key foundational structures that support our goal for all our learners—to be resilient, active, and flourishing students.

The Well Aware Model

Our model comprises two main sections: foundational blocks and key elements of positive mental health.

The model for well-being below provides a framework for our understanding of well-being and for implementing the evidence-based strategies and approaches in our schools and classrooms that give all students the opportunity to achieve well-being.

A Whole-School Whole-Community Approach

With the explosion of information, research, and policies related to mental health, you may be asking:

- What is my role as a classroom teacher?

- What can I realistically do to effectively support my students’ mental well-being?

- How and where do I start?

As educators, we can start by making mental health a priority. That may seem like a simplistic statement, but the more we understand mental well-being and intentionally foster skills and attitudes that support it, the more we can make it possible for our students and ourselves.

When we make the promotion of mental health a priority, it becomes part of our everyday conversations, routines, interactions, and instruction. Research tells us that mental health development and social emotional learning are not secondary to academic achievement —something to fit in when we have time. They are foundational to academic achievement and to nurturing healthy individuals who can navigate life’s challenges and make positive contributions to our communities (CASEL, 2013; Durlak & Weissberg, 2011). Fostering positive mental health is most effective when it is integral to our students’ and our own everyday experiences, inside and outside the classroom.

Making mental health a priority also starts with awareness and knowledge. Problematic behaviour does not necessarily mean that a student has a mental health disorder, and only professionals can diagnose an illness, but there is much you can do by developing the knowledge to support healthy development, identify potential problems, send students on the pathway to care, and ultimately help them develop autonomy over their own mental well-being. As a teacher, you can empower students to make the choices and find the strategies that work for them.

A Teacher’s Role in Supporting Mental Health

- Recognize how your relationship and interactions with students affect their positive mental health.

- Develop awareness and knowledge, using the resources available through schools, boards, and professional development opportunities.

- Know what school resources and community services are available, so that you can turn to them when you and your students need support.

- Implement curriculum-based practices and expectations related to mental health development, and provide direct instruction in key concepts and skills.

- Create a healthy, caring classroom environment for positive mental health for all.

Promoting mental health requires focus and intentionality, but it does not need to be an extra burden. Healthy practices and instruction can be woven into daily routines, and with a whole-school and communitywide approach, you are not alone.

A Social Emotional Learning Approach

So, how can you effectively promote positive mental health? Social emotional learning, or SEL, is one evidence-based approach. According to the Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health (2013), social emotional learning is the process through which children and youth develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills to

- identify and manage their emotions

- set and pursue positive goals

- communicate caring and concern for others

- initiate and sustain positive relationships

- make decisions that demonstrate respect for self and others

- deal with interpersonal concerns and challenges effectively

Adults and youth alike need help to figure out why they feel troubled, how to deal with those emotions, and how to be more effective in relating to others. We all need to develop an effective vocabulary of emotions. When individuals feel troubled but cannot understand or express why and do not know how to deal with anxiety, they are at risk of developing poor habits to release tension, which can lead to mental health problems.

We can all benefit from better skills to identify and regulate our emotions, and understand how our emotions affect our social relationships. Social emotional learning can exist as an intentional, authentic process that is woven into the school culture with common understandings, competencies, and language. All members of the school community, including teachers, education assistants, parents, administrators, consultants, custodians, and bus drivers, can learn to apply SEL language in all their interactions. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning has published research-based evidence of the effectiveness of SEL programs in schools across North America; its evidence of success includes the role of social emotional learning in promoting student academic success and mental well-being (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL], 2013).

Across the country, ministries or departments of education and school boards are applying the principles of SEL evidence-based programs in their learning practices and curriculum materials. Life in the classroom is a rich environment for social emotional function and learning. With daily routines and activities, there are many opportunities for direct instruction in and practice of social emotional skills. A classroom in which all members have SEL skills creates an environment that allows both teachers and students to flourish socially, emotionally, and academically.

Strengths-Based Approach

Another key approach for positive mental health is a focus on identifying and developing students’ strengths rather than fixing their deficits. This approach recognizes that when children and youth are withdrawn or acting out and experiencing difficulties in succeeding at school, we need to understand their circumstances and recognize that they are doing the best they can. When we look closely, we may see that they are demonstrating innate strengths and terrific resilience at getting their developmental needs met. A strengths-based approach acknowledges that we all have inner strengths, capabilities, and resources that can be cultivated to support our well-being.

Resilient, Active, and Flourishing Students

If we ask ourselves what positive mental health looks like, perhaps the best description we can give is an individual who is resilient, active, and flourishing. My experience as a psychologist, parent, and educator has led me to conclude that resilience, commitment to an active lifestyle, and the experience of flourishing through joy in self-realized talents are the essential elements of well-being.

Resilient

To be resilient, we need to believe in our own strengths, abilities, and worth. Resilience can be defined as the ability to cope with life’s disappointments, challenges, and pain. Developing resilience is a particular challenge for adolescents who are dealing with so many physical and emotional changes.

In Duct Tape Isn’t Enough: Survival Skills for the 21st Century, Ron Breazeale (2009) provides an evidence-informed list of skills and attitudes that constitute resilience in children and youth. The five skills are as follows:

- developing effective relationships

- showing flexibility

- doing realistic action planning

- listening and problem solving

- managing emotions

The attitudes Breazeale identifies are these:

- having self-confidence

- seeing meaning and purpose

- holding an optimistic perspective

- keeping a sense of (appropriate) humour

- keeping balance and fitness

- nurturing empathy and making a social contribution

If we think about it, it quickly becomes clear that these skills and attitudes work together. Developing good relationships, communicating effectively, and being flexible and able to plan help to produce a positive self-image and the confidence to tackle a problem with success in mind. These skills also help us to maintain an optimistic perspective and even to find humour in a situation. Likewise, when we feel confident and competent, we enjoy good relationships and we are more likely to take care of ourselves with exercise and a reasonable diet. When we reach out to others in our communities, we feel empowered and optimistic about ourselves and our relationships.

Recent research also supports the importance of the environment in developing resilience (Ungar, 2013). Individuals do develop skills for resilience when they are successfully engaged in school activities, have opportunities to develop positive relationship skills, and strengthen confidence at problem solving. Research further supports the pivotal role an adult can play in helping a student engage in the school environment and access resources needed for success and well-being: see Supporting Minds, authored by the Ontario Ministry of Education (2013). Resilience is possible for all children, providing the resources are available.

Active

The importance of regular exercise in helping to maintain mental and physical health is supported by a robust base of evidence (Otto & Smits, 2011; Ratey, 2008). Research also supports the use of physical exercise to help manage a wide range of mild to severe psychological difficulties among adolescents and adults (Richardson et al., 2005).

In healthy individuals, regular physical activity has been associated with improved interpersonal relationships, social skills, self-image, self-worth, cognitive functioning, and brain composition changes.

At a time when Canadian children and youth spend approximately 62 percent of their waking hours engaged in sedentary activities, including sitting in front of a computer screen (Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, 2011), a conscious focus on physical education and activity in the classroom seems ever so important. Physical education can play a key role in shaping students’ attitudes to a healthy lifestyle—both for now and for their futures.

In our model for well-being, an active lifestyle encompasses regular physical activity for fitness, adequate sleep, good nutrition, and attention to spiritual needs, which may include participation in family, cultural, community, faith-based, or personally enriching activities. The key is to achieve a vital balance in these interconnected aspects of our lives.

Flourishing

The term flourishing describes an optimal level of mental health, regardless of mental illness. In his book Flourish, psychologist Martin Seligman bases optimal well-being, or the experience of flourishing, on five elements (Seligman, 2011):

- positive emotion (fun and enjoyment)

- engagement (passionately absorbed; in the flow)

- meaning (sense of purpose)

- accomplishment (competence)

- positive relationships (connection; valued; belonging)

Ultimately, we can look at mental health promotion in a school setting as an endeavour to promote lifestyle experiences for all students where there are regular opportunities for positive emotion, engagement, meaning, accomplishment, and positive relationships. The explosion of research, as well as school and government initiatives, is providing us with new tools and supports to successfully reach that goal.

What About You? Educator Well-Being

While we focus primarily on students, we cannot overlook the critical importance of your well-being as an educator. In many ways, it all starts with you. If we do not take care—individually, within our school and board communities, and through provincial strategies—to support educator well-being, we are all at a disadvantage. Research shows that teacher well-being supports student well-being (Roffey, 2012). Mental health promotion needs to be a whole-school and whole-community approach, encompassing all of us.

You, as an educator, can enhance your experiences of positive emotion and engagement, a sense of meaning and accomplishment, and positive relationships to support your well-being. It is helpful to note that all of the skills and strategies we consider for students throughout the book can be applied to you as an educator—only the lens is different.

Companion Component

Chapter 1: A Culture of Positive Mental Health

p. 2

Helpful Resources for Tiers 2 and 3

Download PDF (3 pages, 280kb)

p. 9

Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health

http://www.jcsh-cces.ca

p. 10

CASEL Guide

http://www.casel.org/a click on link to guide or search "guide"

click on link to guide or search "guide"

Chapter 2: A Whole-School Whole-Community Approach

p. 22

Mental Health Commission of Canada and the Mental Health Strategy for Canada

http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/  click on Initiatives → Mental Health Strategy for Canada or search “mental health strategy”

click on Initiatives → Mental Health Strategy for Canada or search “mental health strategy”

p. 23

Mental Health First Aid Canada

http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/  click on Initiatives → Mental Health First Aid or search “mental health first aid”

click on Initiatives → Mental Health First Aid or search “mental health first aid”

p. 28

The ABCs of Mental Health

A Project of the Hincks-Dellcrest Centre

http://www.hincksdellcrest.org/  click on Resources and Publications → The ABCs of Mental Health

click on Resources and Publications → The ABCs of Mental Health

p. 29

Children’s Mental Health Ontario

http://www.kidsmentalhealth.ca/

Child and Youth Mental Health Information Network

http://cymhin.offordcentre.com/

p. 35

CASEL Guide

http://www.casel.org/  click on link to guide or search “guide”

click on link to guide or search “guide”

p. 39

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

http://www.camh.ca/

p. 41

Best Start Resources – Open Hearts, Open Minds: Services That Are Inclusive of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Families

Best Start Resource Centre, Health Nexus, Toronto, Ontario, 2013

http://www.beststart.org/  click on Resources → How to resources

click on Resources → How to resources

Egale Canada Human Rights Trust

http://www.mygsa.ca/

p. 44

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Circles and Ways of Knowing

Full Circle: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Ways of Knowing, A Common Threads Resource, Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation, 2012

http://www.osstf.on.ca/  click on Resource Centre → Curricular Materials and Classroom Supports → Common Threads → Projects or search “full circle”

click on Resource Centre → Curricular Materials and Classroom Supports → Common Threads → Projects or search “full circle”

Chapter 3: A Social–Emotional Learning Approach

p. 57

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

http://www.casel.org/

p. 63

Body Map Research from Aalto University

http://www.aalto.fi/en/ search “bodily maps of emotions”

p. 66

Canadian Self-Regulation Initiative (CSRI)

http://www.self-regulation.ca

p. 87

Roots of Empathy

http://www.rootsofempathy.org/

p. 88

International Institute for Restorative Practices in Canada (IIRP Canada)

http://canada.iirp.edu/

Chapter 4: A Strengths-Based Approach

p. 99

Resiliency Initiatives

http://www.resil.ca/

p. 111

Lives in the Balance

http://www.livesinthebalance.org/

p. 122

Stress Lessons Toolkit

The Psychology Foundation of Canada

http://psychologyfoundation.org/  click on Programs → Stress Lessons

click on Programs → Stress Lessons

Kids Have Stress Too!® Program

The Psychology Foundation of Canada

http://psychologyfoundation.org/  click on Programs → Kids Have Stress Too!®

click on Programs → Kids Have Stress Too!®

Chapter 5: Resilient, Active, and Flourishing

p. 135

Best Start Resources – Holistic Support Wheel

Best Start Resource Centre in collaboration with Spirit Moon Consulting, Health Nexus, Toronto, Ontario, 2007

http://www.beststart.org/  click on Resources → Aboriginal child development

click on Resources → Aboriginal child development

Best Start Resources – A Child Becomes Strong: Journeying Through Each Stage of the Life Cycle

Best Start Resource Centre, Health Nexus, Toronto, Ontario, 2011

http://www.beststart.org/  click on Resources → Aboriginal child development

click on Resources → Aboriginal child development

p. 139

Reaching In…Reaching Out (RIRO)

http://www.reachinginreachingout.com/

p. 148

Mindfulness Without Borders

http://mindfulnesswithoutborders.org/

Reaching In…Reaching Out Resiliency Guidebook

http://www.reachinginreachingout.com/  click on Resources → Resiliency Guidebook

click on Resources → Resiliency Guidebook

p. 149

Strength Based Resilience Assessment Tool

http://www.strengthbasedresilience.com/

p. 155

Discovering Strengths Toolkit

http://www.discoveringstrengths.com/

p. 160

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) Guidelines

http://www.csep.ca/  click on Guidelines

click on Guidelines

p. 169

Institute of Positive Education

Geelong Grammar School®

https://www.ggs.vic.edu.au/  scroll to Our School and click on Positive Education

scroll to Our School and click on Positive Education

p. 171

Strengths in Education Project

http://www.strengthsineducation.ca/

Chapter 6: What About Me? Educator Well-Being

p. 182

CASEL Guide

http://www.casel.org/  click on link to guide or search “guide”

click on link to guide or search “guide”

RULER

Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence

http://ei.yale.edu/  click on RULER

click on RULER

CARE (Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education)

A program of the Garrison Institute’s Contemplative Teaching and Learning Initiative

http://www.care4teachers.org/

SMART (Stress Management and Resilience Techniques)

smartUBC, the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus

http://smartubc.ca/

Free Study Guide

This resource will summarize key concepts and points, delve deeper to offer some further resources, provide a checklist to assess understanding that can be used for personal awareness or small-group inquiry, and suggest a well-being focus.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

What Is Positive Mental Health?

Promoting Mental Health

Social Emotional Learning

A Strengths-Based Approach

Resilient, Active, and Flourishing

What About You? Educator Well-Being

CHAPTER 1: Your Role in Student Mental Health

Making Mental Health a Priority

The Teacher-Student Relationship

Mental Health Literacy

Reducing Stigma

The Mental Health Continuum

Teaching and Learning

The Goal of Positive Mental Health

Social-Emotional Learning Outcomes

Creating a Healthy, Caring Environment

A Whole Community Approach

Characteristics of a Healthy, Caring Environment

Strategies and Approaches for the Classroom

Dreikurs and Encouragement

The Power of a Circle

CHAPTER 2: Social Emotional Learning

Social Emotional Intelligence

The Core Competencies

Social Emotional Learning in the Classroom

A Classroom Scenario

Understanding Emotions

Self-Management or Self-Regulation

Social and Relationship Skills

Responsible Decision-Making

Comprehensive Strategies and Approaches

Roots of Empathy

Circles and Restorative Justice

CHAPTER 3: A Strengths-Based Approach—Celebrating Diversity

Some More Than Others: Celebrating Diversity

Strengths-Based Learning

Recognizing and Building Strengths

Promoting Strengths for Mental Health

The Gift of High General Intelligence

The Gift of High Sensitivity

The Gift of Introversion

The Gift of High Activity

The Gift of High Excitement

Diversity and Well-Being in the Classroom

CHAPTER 4: Resilient, Active, and Flourishing

Achieving Optimal Mental Health

Resiliency

What is Resiliency?

Developing Resiliency

What Makes Us Resilient?

Recognizing Resiliency

A Social-Ecological Perspective

Being Active

Physical Activity and Mental Health

Promoting Physical Activity in Schools

Adopting an Active Lifestyle

Flourishing

What Does It Mean To Be “Flourishing?”

Seligman’s Concept of Well-Being

Flourishing, Mental Health, and Mental Illness

Resilient, Active, and Flourishing in Today’s Classrooms

CHAPTER 5: What About Me? Educator Well-Being

Teacher Well-Being Matters

The Value of Social-Emotional Skills

Resources for Educator SEL

Teacher Resiliency and Personal Competence

Self-Awareness

Managing Emotions

Self-Motivation

Empathy

Managing Relationships

A Caring, Inclusive Professional Environment

Teacher Engagement